Sheldon Kopp’s book with this title is definitely worth the read. The title actually comes from the 9th century Chinese Buddhist monk Linji Yixuan. I read it about twenty or more years ago and it was definitely food for the soul. The thesis in this title proposes rejecting external authority and dogma and instead trusting in your own experience and understanding.

In our culture here in the western world, we’ve largely moved away from the worship of an external god. Yes, many still believe and follow religions, but the worship has become more overtly directed at humans. A great example of this is the “Rock Star” of professions like sports, entertainment (actors), leaders and those who obtain large amounts of wealth. We want to follow them, be like them and think about them often when reflecting on our own lives. We also pay a lot of money to hear and see them. We talk about them incessantly and idolize their lives and achievements.

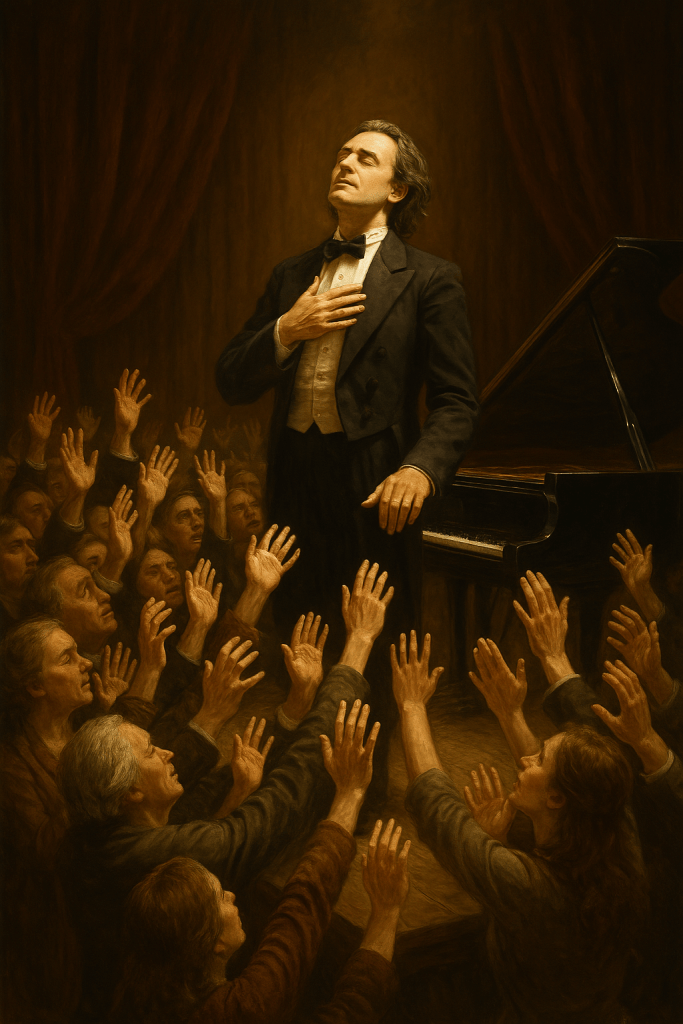

Having been steeped in the classical traditions of piano playing, those “Buddhas” are the composers, the great interpreters/performers, the great teachers that we bow down to. They are like gods to many. We worship the way they play or write music. Of course, great wealth and cult followings envelop these personalities. Historically, one can find concert halls filled with the “who’s who” in the audience: the worshipers. Sometimes the worshipers aren’t even interested in the art form/performance, they are just interested in being part of an experience where they can be seen as appreciating the “greatness” as presented. Even if it isn’t greatness, sometime worshipers follow because others do, wanting to be part of the crowd; sheep following the shepherd. It’s a bit twisted, don’t you think? These perceived giants are just people like everyone else struggling with their own lives. I’m not diminishing the authentic experience of listening to great music and being brought to tears, but how often do you see classical audiences react in authentic ways to the performance. Traditionally, it’s sit still, don’t move, and be quiet for fear you bother someone. It can even be about building Cultural Capital; connections through classical music to be exploited for other purposes.

I remember when the great musician/pianist Chick Corea came to perform at Aeolian Hall for the first time (28 Grammy Awards) and we had dinner together. Chick loved classical music, but he made a statement to me that I’ll never forget:

“Classical musicians take themselves too seriously”.

I asked him to explain this and he reflected on his own journey with classical music (incidentally, this was his greatest passion) and the culture he experienced.

He lamented the inauthentic pursuit of the best performance, the closest adherence to the written text and the elusive “truth” of the very best musician or interpreter of a work. Don’t you dare change a single note or detail the composer has written. It is a sacred text to be venerated and worshipped.

Then there are the composers. Throughout my career I get asked questions like: “who’s your favourite composer….pianist….work of music etc.” “What was the very best performance you ever attended?” Not a lot of talk about how the music or how performance affected your spirit. Authenticity is often completely lost here! It seems like it’s more like “collecting and possessing” than “experiencing and reflecting”. “Oh, that performance in Berlin that I attended of Turandot was certainly rated as the best ever presented…and I was there!” Aren’t I great and special?”

Then there’s the competitions. So many of them now and so many winners. Before international competitions, artists were recommended by their peers for their capabilities and artistry. Now it’s the olympics for the arts. Having art as a competition is antithetical to the creative process.

I worked for years with the great French pianist Cécile Ousset. She sat on the juries of many of the big competitions and had participated in competitions in her youth. I asked her how a decision was made to choose winners. She said: “we choose someone with a lot of experience”. I then asked her: “Why don’t we make competitions for older players who have lots of experience”. She said: “That’s a great idea”.

Completely messed up, right?

I also asked Mme Ousset if the jury ever heard much interesting playing. She said: “no, rarely”. Often Competitions make artists choose winning interpretations rather than their own authentic ones. Playing something in a way that pleases the most or working on technical perfection over spontaneous risk taking.

I hope society can find space for arts for “arts sake”. The creative process as being one of truly “living and experiencing” rather than worshipping and winning. We will all grow immensely and find our creative outlets if we return to building who we are with great authenticity.