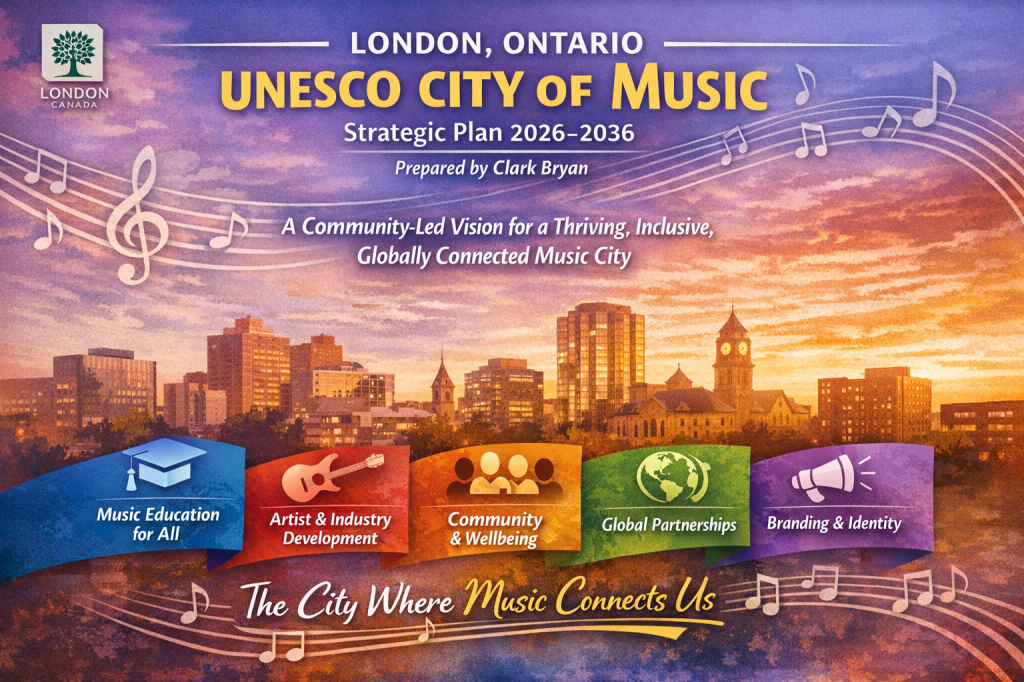

Strategic Plan 2026–2036

Prepared by Clark Bryan

A Community-Led Vision for a Thriving, Inclusive, Globally Connected Music City

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

London, Ontario, Canada’s first UNESCO City of Music, is uniquely positioned to build a future where music is central to community wellbeing, identity, economic vitality, and cultural belonging. This 10-year strategy outlines a community-driven, equity-centred, globally aware approach to transforming London’s music ecosystem into a model for mid-sized urban cultural development worldwide.

The plan is built on five pillars:

- Accessible Music Education for All

- Artist Development & Creative Ecosystem Growth

- Community, Diversity, Intergenerational Connection & Wellbeing

- International & UNESCO Partnerships

- Branding, Marketing & Identity Building for London

The plan prioritizes:

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Newcomer engagement

- Youth leadership & mentorship

- Seniors & intergenerational music pathways

- Mental health & community wellbeing

- Climate-aligned cultural practices

- Collaborative governance & continuous listening

- Financial adaptability & realistic implementation

- A unified, values-driven London City of Music brand

Above all, this strategy affirms that:

Music is not merely an industry — it is a public good, a cultural language, a community asset, and a source of identity and belonging.

Economic development, tourism, and job creation will follow, but the heart of this plan is people, not profit.

1. INTRODUCTION & CONTEXT

1.1 London’s Identity Challenge

London has long struggled with its identity. “Forest City” no longer reflects its rapidly urbanizing, diversifying character. The name “London” competes with a world capital. Despite extraordinary creativity, many residents do not feel a coherent cultural narrative.

London is:

- A city of newcomers

- A city of youth

- A city of seniors and retirees

- A city of deep arts traditions

- A city with grassroots music communities

- A city with world-class learning institutions (Western, Fanshawe, OIART)

The UNESCO designation offers not a brand to adopt , but a story to tell: London is a city where music connects us.

This plan uses music as:

- A unifying civic identity

- A strategy for belonging

- A pathway to cultural empowerment

- A tool for reconciliation and intercultural dialogue

- A wellbeing and mental-health resource

- A catalyst for sustainable urban development

- A bridge to the global community

2. VISION, MISSION & VALUES

2.1 Vision

London is a vibrant, inclusive Music City where every person, regardless of age, culture, income, or identity, an access, learn, create, perform, teach, and enjoy music.

2.2 Mission

To cultivate an equitable, sustainable, community-driven music ecosystem that strengthens London’s identity, supports artists and educators, uplifts mental wellbeing, fosters intergenerational connections, amplifies diversity, and celebrates creativity as a public good.

2.3 Values

- Equity

- Access

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Community Voice

- Cultural Humility

- Lifelong Learning

- Creativity & Innovation

- Mental Health & Wellbeing

- Climate Consciousness

- Collaboration & Partnership

- Transparency & Accountability

- Belonging & Identity

3. STRATEGIC PILLARS

PILLAR 1: ACCESSIBLE MUSIC EDUCATION FOR ALL

Goal: Universal, equitable access to music learning across all ages.

1.1 London Music Education Equity Roundtable

Permanent but rotating body including:

- School boards

- Universities & Colleges

- Community programs (e.g., El Sistema Aeolian)

- Libraries

- Indigenous educators

- Newcomer organizations

- Seniors’ representatives

- Music educators (private and public)

Annual outputs:

- Music Access Map

- Education Gap Report

- Shared-access instrument inventory

- Recommendations to City of Music Council

1.2 Free & Low-Cost Community Programs

- Expand free programs in underserved neighbourhoods

- Subsidize transport + instrument rentals

- Multi-language offerings for newcomer families

- Accessibility supports

1.3 Lifelong & Intergenerational Learning

- Youth pathways

- Early childhood music

- Seniors’ beginner programs

- Family learning streams

- Intergenerational choirs & orchestras

1.4 Music Educator Professional Growth

- Annual summit

- Anti-oppressive practices

- Trauma-informed and adaptive pedagogies

- Cross-cultural repertoire development

PILLAR 2: ARTIST DEVELOPMENT & CREATIVE INDUSTRY SUPPORT

Goal: Empower London’s artists and creative workers to thrive.

2.1 Artist–Educator Residencies

Embed artists in:

- Schools

- Long-term care homes

- Community organizations

- Newcomer centres

2.2 Music Incubation Spaces

- Affordable rehearsal rooms

- Co-working spaces

- Micro recording studios

- Accessible arts facilities

2.3 Career & Business Development

- Entrepreneurship training

- Grant-writing clinics

- Music distribution workshops

- Digital literacy support

- Mental health supports for artists

2.4 Fair Pay Charter

- Minimum recommended fees

- Transparent wage guidelines

- Advocacy for sector labour rights

PILLAR 3: COMMUNITY, WELLBEING, INTERGENERATIONAL CONNECTION & DIVERSITY

Goal: Use music to build belonging, mental wellbeing, and intercultural understanding.

3.1 Neighbourhood Music Activation

- Music in Every Ward

- Pop-up stages

- Community choirs

- Outdoor festivals

- Library and community centre partnerships

3.2 Equity-Centred Programming

- Indigenous-led music initiatives

- Black and newcomer artist development

- LGBTQ2S+ music programs

- Disability-inclusive music practices

3.3 Seniors & Intergenerational Strategy

A core component of London’s Music City identity. Includes:

- Beginner-friendly seniors’ instrumental programs

- Intergenerational choirs

- Seniors-as-mentors initiatives

- Music therapy collaborations

- Cultural heritage ensembles

- Seniors’ music hubs

3.4 Music & Mental Health

- Hospital partnerships

- Music-in-healthcare initiatives

- Youth music therapy pilots

- Senior-isolation reduction programs

PILLAR 4: INTERNATIONAL & UNESCO PARTNERSHIPS

Goal: Strengthen global relationships that benefit Londoners.

4.1 UNESCO Exchange Programs

- Artist residencies abroad

- Educator exchanges

- Co-commissioned works

- Youth global collaborations

4.2 London City of Music Summit

Biennial gathering hosted in London with:

- UNESCO Creative Cities

- Canadian city partners

- Youth delegations

- Community leaders

4.3 Cultural Diplomacy

- Promote London’s diversity

- Showcase London artists internationally

- Build London’s reputation as a global mid-sized cultural leader

PILLAR 5: BRAND, MARKETING & PUBLIC NARRATIVE

Goal: Build a shared identity where Londoners see themselves reflected in the city’s cultural story.

5.1 Brand Concept

London’s new identity emerges from its people:

“London: The City Where Music Connects Us.”

Brand attributes:

- Diverse (especially important perspectives from Indigenous communities)

- Warm

- Community-driven

- Creative

- Intergenerational

- Newcomer-welcoming

- Proudly local

5.2 Internal Marketing (For Londoners)

- “Music Lives Here” campaign

- Newcomer Music Welcome Kits

- Music education directories

- Monthly “What’s On in Music” guide

- LTC bus/poster campaigns

- Neighbourhood activations

5.3 External Marketing (Outside London)

- Target GTA, Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo markets

- Promote London as a music-learning destination

- Cultural tourism itineraries

- UNESCO-branded content

- International student recruitment messaging

5.4 Communications & Storytelling

- Real London stories from youth, seniors, newcomers

- Artist features

- Community-created videos

6. GOVERNANCE, COMMITTEES & COMMUNITY ACCOUNTABILITY

6.1 London City of Music Council

Permanent but Rotating Structure

- 12–18 members

- 2–3-year terms

- First cohort staggered:

- 1/3 serve 1 year

- 1/3 serve 2 years

- 1/3 serve 3 years

Membership Composition Includes:

Artists & Industry

- Musicians (multi-genre)

- Producers/technicians

- Venue representatives

Educators & Academics

- Western University

- Fanshawe College

- Private and community music educators

- Representatives from programs like El Sistema Aeolian

Community Representatives

- Youth (18–25)

- Seniors

- Newcomer representatives

- Indigenous leaders

- Community members (open call)

Institutions & Government

- City Councillor(s)

- Culture Office

- London Arts Council

- Tourism London

For-Profit & Non-Profit Representation

- Both required across the membership

Responsibilities

- Approve annual strategic priorities

- Ensure community-led direction

- Review public input

- Oversee accountability and equity frameworks

- Co-sign UNESCO reports

6.2 Working Groups (Permanent, Rotating Membership)

Standing working groups include:

- Music Education & Lifelong Learning

- Youth Leadership

- Seniors & Intergenerational Music

- Equity, Diversity & Inclusion

- Music Industry & Venues

- Mental Health & Wellbeing

- Sustainability & Climate Action

- International Partnerships

Members serve one-year renewable terms and are selected through open calls.

6.3 Reporting & Accountability

The Music Office must:

- Host annual listening assemblies

- Publish a Music City Dashboard

- Release a public annual report

- Present outcomes to Council, Arts Council, Tourism, and community groups

- Provide transparent budget allocations

7. LONDON MUSIC OFFICE – MANDATE & JOB DESCRIPTION (REVISED)

7.1 Mandate (Community-Led Model)

The Music Office is a facilitator, not a director.

It:

- Listens regularly and deeply

- Synthesizes community priorities

- Supports grassroots initiatives

- Facilitates collaboration

- Reports transparently

- Coordinates cross-departmental efforts

- Ensures community voices guide strategic direction

- Acts as a bridge between community, City Hall, and UNESCO

7.2 Reporting Structure (Collaborative Governance)

The Music Officer reports jointly to:

- City Manager

- Culture Office

- London Arts Council

- Tourism London

This ensures no single agency controls the strategy.

7.3 Music Officer – Full Job Description

Core Competencies

- Deep listening

- Cultural humility

- Facilitation & mediation

- Equity-centred leadership

- Transparent communication

- Strategic visioning

- Community trust-building

Key Responsibilities

Community Engagement

- Continuous consultation

- Sector listening sessions

- Participation in committees

- Direct support to equity-deserving groups

Strategic Stewardship

- Co-create strategic plans with community

- Adapt plans annually through consultation

- Manage UNESCO commitments

Data & Reporting

- Maintain Music Dashboard

- Publish annual reports

- Lead evaluation cycles

Partnerships & Representation

- Work across municipal departments

- Liaise with Arts Council & Tourism

- Coordinate academic collaborations

- Represent London internationally

8. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (3, 5, 7, 10-YEAR)

3-Year (2026–2029) – Foundation

- Establish governance bodies

- Expand free music programs

- Launch seniors’ strategy

- Implement Music Access Fund

- Begin international exchange

- Launch community-led branding campaign

- Deliver Music City Dashboard

5-Year (2030–2031) – Expansion

- Intergenerational hubs in multiple neighbourhoods

- Full Music Incubation Centre launched

- London City of Music Summit

- Youth Leadership Academy

- International partnerships expanded to three cities

- Comprehensive cultural tourism offering

7-Year (2032–2033) – Integration

- Music education accessible in all wards

- Fair Pay Charter widely adopted

- Citywide intergenerational choirs/orchestras

- Five active UNESCO partner cities

- Climate-conscious festival guidelines in place

10-Year (2036) – Maturity & Legacy

- London recognized as global model for community-driven Music Cities

- Fully integrated lifelong learning system

- Intergenerational music as signature London feature

- Strong cultural identity replacing former branding struggles

- Thriving ecosystem supporting thousands of artists

- Deep belonging among Londoners across ages, cultures, and backgrounds

9. CONCLUSION

This 10-year UNESCO Music City Strategy redefines London’s identity around community, creativity, equity, diversity, and belonging.

By centering people over profit, community over hierarchy, and collaboration over control, London can become a Music City known not only for its talent, but for its heart, inclusiveness, and global leadership.

London will be a city where music connects us across age, culture, neighbourhood, and identity. A city where everyone belongs. A city where creativity thrives.

PHASE 4 — SPEECH FOR THE MAYOR / CULTURE OFFICE / MUSIC OFFICE

(Drafted as an example of a public facing vision)

“THE CITY WHERE MUSIC CONNECTS US”

Official Address for the Launch of London’s Music City Strategy

Delivered by the Mayor / Culture Manager / Music Officer

My fellow Londoners,

Today, we begin a new chapter in the life of our city — a chapter shaped by creativity, strengthened by community, and powered by the belief that every voice in London matters.

As Canada’s first UNESCO City of Music, London stands among cities around the world that use culture not as a luxury, but as a foundation for wellbeing, belonging, and identity. Being a Music City is not about spotlight stages or larger-than-life performers. It is about people — about you, your neighbours, your families, your stories, and the sound of a city growing together.

Music connects us. It connects generations. It connects cultures. It connects neighbourhoods. It connects those who have been here for decades with those arriving in London for the very first time.

Our new Music City Strategy is built on a simple but powerful idea: everyone deserves access to the joy, the learning, and the community that music brings.

This plan was shaped by listening — listening to artists, educators, young people, seniors, newcomers, Indigenous leaders, venue owners, and everyday Londoners who want to see their city thrive.

Together, we are building a London where:

- children can learn an instrument no matter their family income

- seniors can rediscover creativity and connection through song

- artists can build sustainable careers

- newcomers can share their culture and find belonging

- youth can lead, innovate, and shape our future

- and every Londoner can feel proud of the city we are becoming

Our identity will no longer be defined by confusion or comparison. We are not simply “London.” We are London: “The City Where Music Connects Us”.

This is our sound. This is our story. And it belongs to every one of us.

Thank you for being part of this moment. Let’s build this city together, in harmony.

PHASE 6 — THE MUSIC CITY PLEDGE (For Citizens & Organizations)

THE LONDON MUSIC CITY PLEDGE

I believe that music belongs to everyone. I commit to listening with openness, creating with joy, supporting artists and educators, welcoming diverse voices, and helping build a London where every person can learn, share, and thrive through music. Together, we make London the City Where Music Connects Us.